Home Page Papers by Peirce Peirce-Related Papers

TO BOTTOM OF PAGE

Disciplinary and Semiotic Relations across Human-Computer Interaction

Ph.D. Thesis (excerpts)

by

Luiz Ernesto Merkle

Graduate Program in Computer Science / Faculty of Graduate Studies

The University of Western Ontario

London, Ontario, December 2001 / This work was supported by CNPq

Abstract

This thesis discusses the multifaceted nature of Human-Computer Interaction through dimensions associated with disciplines in the sciences and engineering (information technology), the social sciences (people and society), and the arts and humanities (interaction and communication), and proposes a three-dimensional conceptual framework. The proposed framework is a three dimensional conceptual chart in which disciplinary relations can be visualized and explored. It is is used to chart the historical disciplinary boundaries of both informatics and HCI and their expansive or retractive tendencies, showing a chasm between Informatics' and HCI's theories and their actual footprints. This chasm is a motivation for an in-depth exploration of a small part of Peirce's work, the foundations of Semiotics.

The thesis structure includes topics across several disciplines, shifting from an exploration of the narrowing tendencies of Informatics (mostly product driven), passing through the broadening goals of HCI and Software Engineering (mostly human and management driven, respectively), and finally reaching the foundations of Peirce's Semiotics (necessarily ethically and esthetically driven).

Abstract relations are fundamental to a deeper understanding of Peirce's work, including semiotics. However, consensus on Peircean sign relations has been achieved neither in semiotics nor in its applications to informatics, being often in contradiction to it.

In order to establish solid foundation between HCI and Semiotics, this thesis concludes with a systematization of the structure of Peirce's sign relations with the aid of tools developed in Informatics, stressing their relational and open characteristics. In particular, it discusses sign relations and derived categories as mathematical lattices. Multi-dimensional Hasse diagrams are introduced and used to structure and visualize both sign relations and relations among their categories. Existing diagrams are shown as particular cases of the proposed solution, illustrating its expressiveness.

Key words

Design, Process Models, Curricula Recommendations, Human-Computer Interaction, Informatics, Interdisciplinary Relations, Peirce, Semiotics, Sign Categories, Classes of Signs, Sign Relations

Contents

Certificate of Examination

ii

Abstract and Keywords

iii

Acknowledgements

vi

Table of Contents

viii

List of Tables

xi

List of Figures

xii

Preface

xvii

I Cultural Ecology of Informatics and HCI

1

1 Informatics' Disciplinary Diversity

2

1.1 Introduction

3

1.2 Disciplinary Diversity across History

5

1.3 Development of Professional Associations

9

1.4 Emergence of Informatics

14

1.5 Consolidation of Informatics

21

1.6 Excess of Disciplinary Segmentation

24

1.7 Renewal and Reorganization

32

1.8 Summary and Final Remarks

41

Bibliography

43

2 Human-Computer Interaction

49

2.1 Introduction to the Cultural Ecology of HCI

50

2.2 In the Search of Theoretical Foundations

53

2.3Disciplinary Diversity across HCI

59

2.4 Conceptual Charts and Disciplinary Scope

63

2.5 Computers + Humans

74

2.6 Humans + Computers + Interactions

85

2.6.1 Stakeholders' Relations across HCI

91

2.6.2 HCI 3D Conceptual Framework

102

2.6.3 Examples: Disciplinary Trajectories across History

104

2.7 Summary and Final Remarks 2

111

Bibliography

114

3 Design Processes

127

3.1 Models of Communication

129

3.2 Interactive Machines

137

3.3 Interaction Models in HCI

142

3.4 Diffusion as Cultural Transformation

152

3.5 Models of Organizational Processes

162

3.6 Towards a Model for Design Processes

182

3.6.1 Some Archetypal Examples

188

3.7 Summary and Final Remarks 3

204

Bibliography

206

II Order in Peirce's Sign Relations and Derived Categories

214

4 Sign Relations and Categories

215

4.1 HCI and Communication

216

4.2 Sign Relations

222

4.3 Ternary Sign Relation in Informatics

231

4.4 Categories of Ternary Sign Relations

233

4.4.1 Partially Ordered Sets and Spaces

252

4.4.2 Relations of Order among Categories of Signs

263

4.4.3 Derivation of diagrams of the ten categories

269

4.4.4 Categories derived form different enumerations

276

4.5 Decadic Sign Relations

280

4.5.1Categories of Decadic Sign Relations

287

4.5.2Comments on other existing diagrams

300

4.6 Summary and Final Remarks 4

304

Bibliography

307

5 Looking Across and Looking Along: Reflections

312

III Appendices: Additional References

324

A Informatics

325

B Software Engineering

335

C Human-Computer Interaction

342

D Cognitive Sciences

350

E Communication and Semiotics

359

F Curriculum Vitae

370

Preface

Information technology is deeply related to literacy and numeracy, enabling people to communicate, to interact with others and with the world in proactive, reactive and mediated ways, to intervene in the world they live. Information Technology affects society, for better or worse. The associated emergence of new professions, occupations, areas of expertise, research topics, merchandise, as well as the transformations of people's daily lives (either because they have access to such technologies, or because they do not) is not necessarily recent, but awareness for these issues have increased across the turn of the century.

Fields in Information Technology, such as computer engineering, computer science, and information systems are recognized and established within academic, industrial, commercial, and governmental institutions. Nevertheless, what was new and emergent a while ago became traditional and consolidated. Although communities in these fields have helped to overthrow the previously established order, the actual cultural transformations went beyond their niches of expertise. However, it is not possible to remain as such. There is a crevasse between the way Information Technology is woven across societies and the way it is understood within the same professions that have developed it. While computers are deeply transforming communication, the main theoretical frameworks still construe computers as isolated abstract machines.

These fields have identities linked with innovation, entrepreneurship, leadership, to mention a few, but no longer determine alone the blueprints of Information Technology. The transformations that these now orthodox communities helped to foster are deeply echoing across their own foundations and current practices, questioning their professional disciplinary niches. It is possible to understand professions across Information Technology as completing a first cycle, a cycle of initial consolidation, of initial recognition. But this has only been a first one among the many yet to be undertaken.

The more and less traditionally involved communities will have to transform their practices, their theories, and their praxis according to their social and ethical rights and responsibilities. As more and more fields emerge to fill the gaps left by traditional domains of expertise, professionals, researchers, educators, and policy makers, who have their lives structured around certain world views, face the challenge of being on the crossroads between the new and the old. The further development of Information Technology demands an openness and an integration of the computing artifacts with their context.

The mentioned crevasse is slowly being challenged and bridged, but changes are simultaneously fantastic and threatening. They are fantastic because they show how fruitful the technological interventions have been across societies. They are threatening because this same fruitfulness appears to dislodge some of its forerunners, mostly if their traditional prescriptions turn to be ineffective in current situations or have unexpected consequences. The emergence of new fields and new responsibilities put traditional identities into question, triggering responses that go from the most revolutionary to the most reactionary.

For example, the relation between people and technology, in its many scales and time frames, has indeed attracted interest on issues that have remained dormant during the consolidation years of Information Technology. Similar interests have nurtured the development of fields such as:

Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) and Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), with their emphases on people's activities; Computer Semiotics and Organizational Semiotics with a focus on meaningful design; Software Engineering and Organizational Learning with foci on the management of technology production and maintenance; Electronic Commerce, Distance Education, and the Social, Ethical, and Legal aspects of technological interventions and their critical appraisal. A link between the study of computers and the study of language is not new. Throughout the history of Information Technology there are many cases in which the cross-pollination between numeracy and literacy, and between computing and communication has been present. It is enough to attempt to imagine a hypothetical computer science developed without computer languages. In order to imagine a similar scenario, we would have to travel back half a century or more to a time in which computers were not ``programmed'', but wired, and also forget earlier related work on algorithms and automation.

Indeed, the link between computing science and linguistics lays at the same venue as the above mentioned crevasse. Following a legacy that dates back to the strong link between linguistics and formal languages, the disciplinary barriers that separate developers from users, and closes the computer to the outside world is not only in close consonance with the study of language as structure, but also in contradistinction to the study of language as activity, as utterance, as use. As language, Information Technology is meant to be effective in use, and not only as form.

The thesis is intended to to give a small contribution to a broader understanding of ``Informatics'' as a multifaceted open discipline, one that is committed to several disciplines, and may involve a myriad of other ones. I will use the term Informatics to stand for this heterogeneous field still in construction, which in my perspective includes current disciplines such as Information Technology and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI).

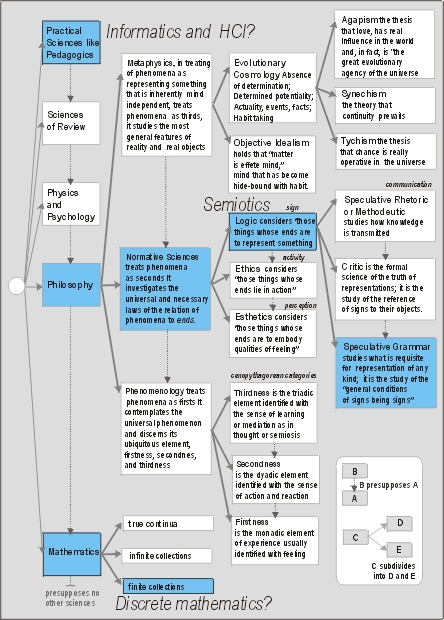

As a path towards a broader understanding of Informatics, the thesis explores the nature of HCI and its disciplinary ecology having part of Charles S. Peirce's work as a backdrop. Peirce's systematic philosophy illustrated in Figure1 spans across a scope broader than most approaches that study language and communication.

Figure 1 uses an arborescent diagram to illustrate both the segmentation of Peirce's systematic philosophy and what each branch presupposes. For example, Semiotics (also called Logic) presupposes Ethics and Esthetics. That is not necessarily the case in Semiotics as developed throughout the twentieth century by all of Peirce's followers and by other schools of thought. Scholars and scientists have the tendency to stratify, pigeonhole, and linearize their disciplines as if they were unconnected, and this can be identified both in Informatics and in Semiotics.

Figure 1 : Peirce's Systematic Philosophy: based on the introduction in Peirce et al. (1991)

Figure 1 graphically depicts a description of Peirce's evolutionary philosophy written by the editors of a recent collection of his writings (Peirce et al., 1991), which also included the following comment:

Peirce's philosophy is thoroughly systematic - some might say it is systematic to a fault. Central to his system is the idea that certain conceptions are fundamental to others, those to still others, and so on; so that it is possible to analyze our various theoretical systems (our sciences) into a dependency hierarchy. At the top of this hierarchy (or at the base if we envision a ladder of conceptions) we find a set of universal categories, an idea Peirce shared with many of the greatest systematic thinkers including Aristotle, Kant, and Hegel. Peirce's universal categories are three: firstness, secondness, and thirdness

I have structured this thesis in two main interrelated parts. Part I, which includes Chapters 1, 2, and 3, explores the cultural ecology of Information Technology and Human-Computer Interaction. Part II, which includes Chapter 4 and the conclusions, explores the problem of order in sign relations and derived categories, and discusses future work, respectively.

Within Figure 1 I would locate Informatics and HCI as a practical science, located at the top of the diagram. For Peirce, practical sciences, such as pedagogics, presuppose all other fields. This is in agreement with the fact that HCI presupposes psychology, for example. In its current forms, HCI does not always presuppose knowledge transmission or mediated activities.

Part II, however, would be located mostly at the bottom part of Figure 1 and deals with the relational structure of signs and categories of signs. In between top and bottom, there is a huge crevasse that needs to be explored more deeply if one intends to develop semiotic foundations for HCI/Informatics. Without being comprehensive, I have attempted to develop this thesis in close resonance with Peirce's rationale, which does not assume that Peirce was completely right.

The thesis title is a reference to these two extremes. On the one hand the thesis explores the still et loose disciplinary relations that structure the field of Informatics/HCI as an heterogeneous arena. On the other hand it explores the relations of order that structure the core elements of its foundations, but always having Peirce's related work on the horizon. I should remark that as Informatics/HCI matures their horizons will also change.

Chapter 1 explores the development of Informatics' disciplinary diversity. This exploration includes topics such as the specialization of Informatics into just a few disciplinary branches. This specialization increased the depth of certain subjects at the expense of loosing part of Informatics' initial breadth. In the proposed conceptual framework, which is completed only in Chapter 2, disciplinary segmentation is visualized with the aid of divergent constellation of interests that have consolidated different but not necessarily nonintersecting niches of expertise. Some other related areas focused on what was out of focus in Informatics, but they are not usually listed as part of it.

Chapter 2 explores Human-Computer Interaction as an example of such a divergent disciplinary force. In both Chapters 1 and 2 information gathered from curricula recommendations and professional opinions illustrates how these fields have narrowed their scope to small disciplinary niches, leaving spaces for other fields to develop. The development of Computer Supported Cooperative Work in contraposition to HCI is an example. However, models of HCI's subject matter have not been comprehensive enough to capture this and other diverging tendencies. With this comprehensiveness as a goal, a multi-faceted model of HCI's cultural ecology is proposed and briefly exemplified. An ecological approach that describes disciplinary niches and their relations is intended to foster both disciplinary diversity and openness towards what is different. The description of the ``cultural ecology'' of an area involves the demarcation of the scope and depth of its disciplinary niches, which includes the identification of interfaces, barriers, and strength of connections between them, awareness for unexplored regions, and so on. In this sense, the proposed model enables the mapping of actual or aimed limits and foci of the disciplines or areas that currently compose a certain field. The model is intended to provide a more detailed description of the current complexity found across HCI and Informatics, at least considering the perspective adopted here. For example, with aid of this multifaceted model, it is possible to visualize the decrease in scope that went from organizations to individuals when the popularity of personal computers surpassed mini and mainframe computers (data processing). This enables a more complete, but not yet comprehensive, account of their history.

The proposed model is structured within dimensions associated with technology, people, and interactions. It has been developed in light of Peirce's work. Most approaches in informatics still model computers as closed isolated machines. If mapped into Peirce's philosophy this would correspond to mathematics as finite collections of elements. I am aware of the dangers of working between disciplines. The following examples are intended to acknowledge that the development of informatics/HCI can be mapped as a trajectory across Peirce's philosophy. In other words, Peirce's work is a suitable candidate to scaffold theory building in HCI/Informatics. When one talks about the phenomenology of user-oriented or user ``friendly'' friendly systems there is reference to feeling, which would be almost at or at the level of firstness (feeling), respectively. Artifact human-centeredness as developed in HCI, is usually restricted to individual computers and individual users. Norman's gulfs of execution and evaluation would be at the level of secondness (action and reaction). Approaches that emphasize the role of technology as mediation, such as Computer Mediated Communication would be mapped around thirdness (mediations in thought).

The trajectory of genres of interaction also drifted from the simple but ``abstract'' level of command languages (thirdness) past the ``concrete'' level of direct manipulation (secondness). Currently, there are mixed genres. Similar analysis could be carried out at the level of Peirce's Normative Sciences, and different approaches could be mapped according to the common focus on perceptions, activities, or representations. With the danger of being repetitive, I should remark that such a classificatory approach easily enters into a dead end. The importance of Peirce's philosophy is its relational character. Peirce's categories are not existential. When one classifies a certain sign into a certain category one is saying that it is of a certain kind at that moment and situation. Basically it is in a certain state, but at another moment it can be classified within another category or state. In this sense they can be an interesting framework to explore thought as action and design as interaction.

Chapter 3 further complements the conceptual framework with the notion of process. It emphasizes the dynamic, open, relational and non-periodic nature of computational and communicative processes. It also illustrates how both interaction and process models used across HCI and Software Engineering have restricted a scope, and are often reductionist. The waterfall, the spiral, and prototyping design process models have different constellations of interest, varying in foci and breadth. Overall, they usually emphasize development rather than both development and use. The process model is intended not to be prescriptive in the sense of scheduling design activities. Nevertheless, it prescribes a space for possible design activities which can chaotically oscillate between activities usually associated with development and use. At a glance, the process model introduced in this chapter seems to be in close consonance with Peirce's Evolutionary Cosmology, in which absence of determination presupposes habit. Further research needs to be carried out on this subject.

Chapter 4, the sole chapter in Part II, has a different approach. The thesis has until this point adopted a broad but somewhat shallow perspective considering Peirce's philosophy. The reader interested in HCI approaches such as distributed cognition, semiotic engineering, computer semiotics, language/action, and theory of activity may be disappointed that I have not explored these approaches in more detail. With varying emphases on purposeful perception, action, and representations, these approaches would be at the level of the normative sciences and would presuppose Peirce's phenomenology. Chapter 4 explores Peirce's concepts of signs and the associated sets of derived categories. In Peircean Semiotics (logic) a sign relation is triadic, but it can be refined into a decadic one. Categories of signs are obtained from the correlation between a sign relation and the cenopythagorean categories, the subject of Peircean phenomenology. The full development of a Peircean semiotic foundation for HCI would demand at least the consideration of issues that span the level of how knowledge is transmitted (Speculative Rhetoric). As suggested by the diagram, full foundations for HCI/Informatics would demand the consideration of the whole diagram. Both options are too broad to be carried out in a Ph.D. thesis.

Consequently, I focused on the most fundamental and narrow topic within Peirce's related work, which deals with finite collections of elements. With that choice, I was still able to envision the breadth of the involved foundations, leaving the door open to future research, but was able to deepen its most fundamental core. The chosen scope coincides most with the theoretical realm of Computing Science, in which several formalisms and structures have been developed to explore relations between finite sets of elements (data structures). In it, the relational structure of both sign relations and derived categories are understood as lattices, not a completely novel idea, and visualized with multi-dimensional Hasse diagrams. Several diagrams found in the literature turn out to be special cases of the proposed solution, facilitating their comparison and illustrating its generality.

This thesis represents only a first small step towards the development of a full-fledged conceptual framework for HCI/Informatics. It was not intended to be comprehensive, but rather to foster both an encompassing overview of the involved issues and more solid foundations.

I would say that professionals in Informatics and HCI, broadly understood, have a challenging task ahead. Their perspectives have grown limited but are claimed to be universal, turning other fields into mere applications. It is still a product driven discipline. Let Informatics and Human-Computer Interaction grow. Let it be driven by the way people live.

Part I

Cultural Ecology of Informatics and HCI

Chapter 1

Informatics Disciplinary Diversity

1 Informatics' Disciplinary Diversity

2

1.1 Introduction

3

1.2 Disciplinary Diversity across History

5

1.3 Development of Professional Associations

9

1.4 Emergence of Informatics

14

1.5 Consolidation of Informatics

21

1.6 Excess of Disciplinary Segmentation

24

1.7 Renewal and Reorganization

32

1.8 Summary and Final Remarks

41

Bibliography

43

[...]

1.8 Summary and Final Remarks 1

The academic communities directly associated with informatics have varied their scope in order to grow across a significant part of their development. This chapter explores the historical development of informatics using the trajectory of major professional associations, curricula recommendations, and the related literature. It illustrates how it is that such an innovative field turned into a conservative one.

Informatics' consolidation or growth is usually associated with the great depth that its communities have developed within certain subjects. Throughout this historical process of consolidation, the involved communities raised many barriers and bridges that end up structuring the field of Information Technology, as well as the field of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). By narrowing the kind of phenomena disciplines such as computer engineering, computing science, and information systems comprised, these communities have been able to consolidate themselves as established fields of knowledge. Interests in cybernetics, systemic approaches, linguistics, and anthropology have been slowly left out of the core issues of the profession. Computer Engineering, Computing Science and Information Systems developed narrow but complementary constellations of interests focused on hardware, software, and systems, respectively. This decrease in diversity and increase in focus may have been appropriate in the past, but it should be revised in the future. Awareness of this dynamics can help the reorganization of informatics as a whole, including a better understanding and appraisal of the roles that some recently emerged fields can play.

One of the issues that I addressed in this chapter is intended to shed some light on how an often vibrant field such as Informatics eventually produces narrow-minded professionals. The expanding nature of informatics and its successes are not enough to justify the over-specialization of its professionals. Indeed, Informatics has reached a point at which a non-reflective practice may hinder its development.

The development of a field, a profession, a discipline, a research topic happens not only at its center or focus, but also on its boundaries and beyond them. Current research trends and professional criticisms can be characterized as having or demanding foci that go beyond Informatics' recognized technical dimensions. For example, a product centered design can be enriched with perspectives that stress not only the connectedness between product and process, between management and project size, between interests and consequences among development, use, evaluation, and disposal, but also the consequences of remembering and forgetting, seeking and discarding, teaching and learning, developing and using. It interweaves the imaginary with the concrete, making possible for designers to make their dreams become reality via a negotiation with materials.

Considering the period after the 1980s, the profession of informatics has been increasingly concerned with human issues by the direct inclusion of individual and collective issues in fields such as Human-Computer Interaction and Computer Supported Cooperative Work, or by indirect reference to managerial and economic issues in fields such as Software Engineering and Electronic Commerce.

Although Informatics promises easy to learn and use technology, phenomena associated with cognition and communication have not been the foci in which mainstream Informatics has developed greater depth. The recent increase of Informatics' footprint demands the exploration of new realms, what can be facilitated through cross-pollination with disciplines that have been studying these realms for some time. Indeed, several new professions and occupations related to informatics have emerged, bringing heterogeneity to it, and forcing a disciplinary reorganization.

As I have said, some of these endeavors have been forgotten in the past. But, absorbed, transformed, or discarded, they have continued to play a role in subsequent stages of professional development. Currently, fields such as bio-computation, computer algebra, medical informatics, software ergonomics, software engineering, human-computer interaction, computer-supported cooperative work, computer semiotics, computer mediated education, information management and retrieval, social informatics, computers and law, electronic commerce, and web-services design have their strength exactly grounded on the cross-pollination from two or more apparently autonomous traditional disciplines.

From a Peircean perspective, the theoretical understanding of computing is still an isolated phenomenon, restricted to the realm of an isolated machine. Exceptions point to interactive machines, and towards a shift from product driven design processes to human driven ones, what adds a second facet to Informatics, and leads to the second chapter.

The main contribution of this chapter is the introduction of a multidimensional model that enables the graphic representation of disciplinary constellations of interests. In this chapter only the technological dimension is explored in respect to how it has developed.

Each dimension and corresponding scale can be used to differentiate different perspectives or interests.

Chapter 2

Human-Computer Interaction

2 Human-Computer Interaction

49

2.1 Introduction to the Cultural Ecology of HCI

50

2.2 In the Search of Theoretical Foundations

53

2.3Disciplinary Diversity across HCI

59

2.4 Conceptual Charts and Disciplinary Scope

63

2.5 Computers + Humans

74

2.6 Humans + Computers + Interactions

85

2.6.1 Stakeholders' Relations across HCI

91

2.6.2 HCI 3D Conceptual Framework

102

2.6.3 Examples: Disciplinary Trajectories across History

104

2.7 Summary and Final Remarks 2

111

Bibliography

114

2.7 Summary and Final Remarks 2

Educators have been discussing the importance of certain trends and the appropriateness of research directions since the inception of informatics.

Any research, development, or reflection that intervenes across the field as a whole, within a particular specialization or area, or even in a single individual at a certain moment, is either transforming or sustaining human values associated with them. Across informatics and HCI, it is possible to find many publications addressing disciplinary relations. Several of these endeavors explore specific relations among two or three disciplines. A small number of publications have addressed design as communication, bringing to informatics reflections developed in linguistics, hermeneutics, semiotics, cultural and historical psychology, and language studies, among others. Among the many available options as foundations for a communicative facet of Informatics and HCI, this thesis proposes the related work of Charles Sanders Peirce, known as the forerunner of both Semiotics and Pragmatism.

Disciplinary boundaries are necessary for the consolidation of disciplinary niches, which include the sustainable development of communities, practices, theories, attitudes, identities, policies, and so on. What is appropriate or not, on what tenets it is centered, where one discipline ends and another begins, whether two or more disciplines intersect or whether there is a gap between, what should be given priority in a subject, and when should a certain subject be given priority, together of many other issues, have been the motivation not only of arguments and quarrels among different currents of thought and practice, but also discussions of the advantages and strengths of interdisciplinary endeavors, despite the associated challenges. The differences in perspectives of where a field starts or ends, towards or from where it should expand or retract, or in consonance or contradiction with whose interests or what vary considerably. These limits vary across people, across schools, across countries, across history. The professional challenge is to achieve unity among this diversity. I refer to the diversity of emphases that structure a certain field its constellation of interests.

This chapter focuses on disciplinary relations and disciplinary diversity across the historical development of the field of Human-Computer Interaction. The field of Human-Computer Interaction has been characterized many times as a field spanning boundaries due to the large number of disciplines that have contributed to it. The communities in HCI have slowly recognized the importance of disciplinary diversity across its foundations. In this sense, HCI communities are a phase ahead of traditional fields in informatics, which have only recently faced the challenge of a diversity that has since been forgotten.

Nevertheless, HCI has not been immune to the historical disciplinary forces that constitute its disciplinary grounds, such as the cognitive and the computer sciences. This influence is visible in the main models that discuss HCI's nature, with a clear bias in favor of dyadic frameworks that emphasize the single user of a single computer. Using a disciplinary chart, I propose a conceptual model of HCI's constellation of interests that also emphasizes other tendencies present in its cultural ecology.

A three dimensional model is progressively built with the inclusion of additional facets respectively linked to technology, people, and their interactions, which is in consonance with Peirce's systematic philosophy. I have four main goals with this representation or model. Firstly, I want to compare different areas in a single diagram. Secondly, by showing the simultaneous presence of more than one perspective on a single discipline, I would like to facilitate the interdisciplinary work among Informatics' disciplines and with other disciplines. Thirdly, I would like a method that could be used with other or more dimensions than the ones discussed here. And fourthly, I intend to facilitate the characterization of computer semiotics within Informatics, in order to delimit the scope of the second part of this thesis.

In this conceptual framework, visualized as a multi-dimensional disciplinary chart, distinct constellations of interest can be compared in relation to established academic fields. In the charting of HCI and informatics, I have used three basic dimensions, which encompass the organizations of (i) artifacts, (ii) humans, and (iii) interactions. I have chosen these three dimensions in accordance with my objectives of describing the cultural ecology of HCI, the role of the humanities in it, and in particular, the role of communication in close resonance with Peirce's work.

These dimensions correspond roughly to the foci of disciplines such as (i) computer engineering, computer science, and information systems in a first group; (ii) physiology, psychology, anthropology, and sociology in a second group; and (iii) linguistics, language studies, and media and cultural studies in a third group. A focus on computer architecture would be narrower than a focus on net-centric computing, but a focus on engineering telecommunications, despite its usual broader physical scope, would be even narrower because telecommunications is only a part of a network.

A close analysis of each of these dimensions or disciplines shows that they are not as isolated as they first seem. For example, in the history of informatics many disciplinary joint works can be identified, such as, automation and cybernetics (control systems), engineering and management (management systems), automation and linguistics (automatic translation), mathematics and linguistics (either programming languages or theory of computing), artificial intelligence and psychology (cognitive sciences), etc.

Nevertheless, I should remark that I have limited the scope of this chapter to the charting of disciplinary relations, exclusively. I do not discuss the value of, the motivations for, or the effectiveness of such disciplinary relations. Despite their importance, I have limited myself to chart such barriers and bridges within a multifaceted model. Within this delimitation, I have left out many important issues discussed in the literature, such as the difficulties, advantages, and political consequences of these disciplinary relations.

The conceptual framework and its visualization are enough expressive to depict the history of HCI at a higher level of detail than it is usually described, showing that although it continues to expand, the expansion is not monotonic and present phases of retraction.

Technology has a purpose. Therefore, in relation to Peirce's work, in which interactions and representation are important facets, technology would necessarily link phenomena to ends, reaching at least the level of the Normative Sciences. HCI, would go beyond Peirce's philosophy because it presupposes Psychology, which presupposes it.

Chapter 3

Design Processes

3 Design Processes

127

3.1 Models of Communication

129

3.2 Interactive Machines

137

3.3 Interaction Models in HCI

142

3.4 Diffusion as Cultural Transformation

152

3.5 Models of Organizational Processes

162

3.6 Towards a Model for Design Processes

182

3.6.1Some Archetypal Examples

188

3.7 Summary and Final Remarks 3

204

Bibliography

206

3.7 Summary and Final Remarks 3

Throughout this and the earlier chapters, I have stressed the importance of concepts related to agency, communication, and interaction to processes of design in HCI and Informatics. This chapter is intended to rescue and further develop some of the richness found in design processes, which are non-linear, parallel, and heterogeneous. From a Peircean-informed perspective, design processes would be necessarily bound with habit, but simultaneously would not be deterministic (Evolutionary Cosmology).

However, most process models in Informatics, including the ones in HCI and Software Engineering, tend to be mostly deterministic in their prescriptions, and are restricted to the realm of developers in contraposition to the realm of users.

In this chapter I gave several examples of process models that use concepts similar to the ones developed in semiotics and communication studies. Dichotomies such as subject and object, the new and the old, internalization and externalization, the global and the detailed are examples.

When seen from the lens of design as communication, design lifecycles show clearly who interacts with whom across organizational processes. In the history of informatics models of design processes have been slowly including activities and stakeholders that have been previously abstracted away or simply ignored. Nevertheless, the systematic exclusion of some stakeholders or activities is deeply entrenched in the established cultural ecology. I discuss how processes of design and deployment are deeply related to the established cultural ecology of informatics. For example, those who come last in the usual sequence of technology production are usually ranked lower in terms of status. Based on several models of organizational processes I further complement the HCI conceptual model with the notion of process. With these limitations in mind, a process model is proposed and discussed with the aid of the Lorenz attractor. I should remark that this process model is not a meta-model.

However, it is expressive enough to encompass some existing models, thereby facilitating a graphic comparison between their scope. I discuss several process models in software engineering to illustrate its expressiveness.

Researchers in software engineering, usability studies, human-centered design, situated and mediated understanding of technology and cognition, among others, have recognized the limitations of formal approaches in technology design and evaluation and have attempted to go beyond them with different alternatives.

Several of the organizational and process models presented indeed make reference to concepts widely studied in semiotics. However, very few authors acknowledge that these concepts have been studied elsewhere. Their attempts are evidence of the need to close the crevasse between the sciences and the humanities, between professional activities related to information and computation, and between scholarship in communication and the practice of design.

With this chapter I close the discussion about the cultural ecology of Informatics and HCI. This has only been a start, however, in which I proposed a rough model of the disciplinary relations and the associated dynamics present across these fields. At several points across these three initial chapters I have pointed to the scant recognition that communication, broadly understood, has received both in HCI and in Informatics.

Michel Serres (1980) uses the metaphor of the Northwest Passage to describe the dangers of the ever changing path that links science with literature. I close these three initial chapters in the hope that the overview of the cultural ecology of Informatics gave the reader a feeling for its heterogeneity and for the challenge that its development will be.

In the next chapter I explore a tiny stretch of this intricate passage. I explore the structure of the sign, as proposed by Peirce, in what concerns the partial order of its elements. I do that with the aid of structures developed in the realm of the computing sciences, mostly in the field of data structures. The concept of the sign relation is the unity of analysis of Semiotics. For example, syntactics, semantics, and pragmatics have their origin in the organization of such a relation, but assume a different organization. The same can be said about data structures, which are fundamental structures in Informatics. The work reported in Chapter 4 is classified neither as computer science nor as semiotics as they are recognized today, but as both.

Part II

Order in Peirce's Sign Relations and Derived Categories

Chapter 4

Sign Relations and Categories

4 Sign Relations and Categories

215

4.1 HCI and Communication

216

4.2 Sign Relations

222

4.3 Ternary Sign Relation in Informatics

231

4.4 Categories of Ternary Sign Relations

233

4.4.1 Partially Ordered Sets and Spaces

252

4.4.2 Relations of Order among Categories of Signs

263

4.4.3 Derivation of diagrams of the ten categories

269

4.4.4 Categories derived form different enumerations

276

4.5 Decadic Sign Relations

280

4.5.1 Categories of Decadic Sign Relations

287

4.5.2 Comments on other existing diagrams

300

4.6 Summary and Final Remarks 4

304

Bibliography

307

4.6 Summary and Final Remarks 4

In the history of HCI and informatics, the social sciences have contributed to human-centered perspectives through disciplines such as psychology, anthropology, and sociology. However, the disciplines that have studied human communication for the longest are not the ones in the social sciences, but the ones in the arts and humanities. Languages have been key to the development of informatics. Similar to the development of linguistics and language studies, this contribution has emphasized only language structure, rather than both structure and use. However, a broader understanding of human communication in informatics, one that includes language use, has received scant recognition until now. In this thesis, I only point to this unexplored subject.

I understand that the cross-pollination between informatics and semiotics will be feasible only if the participant fields are able to establish a common ground across the complementarity of their differences. The challenge is that there has been no common ground regarding what communication is in either field.

Through the research I have carried out in this dissertation, I realized that it was not enough to import models of communication that have been developed in the arts and humanities if these models were as stiff as the ones developed and used in informatics and the cognitive sciences. In semiotics, there has been a strong tendency toward linear sequential models. Peirce went beyond this tendency, but has not been well understood. Today, there is no agreement on how to represent a sign relation. I am not talking about the rivalry between different schools: even within schools, confusion reigns on how to organize the components of a sign relation syntactically.

Instead of scanning across different topics across HCI and informatics, I explore a topic that is related to the fundamentals of Peirce's Systematic Philosophy. The main contribution of this chapter is a systematization of a fundamental problem in semiotics, that is, how to structure the unity of analysis of semiotic processes, which is the sign relation. Peirce is considered to be a forerunner in the development of semiotics as understood today. His work is also considered a precursor to pragmatism. The size and diversity of Peirce's writings is challenging.

But within a wild heterogeneity, very coherent principles structure the subdivision of the several areas of his work, and what they presuppose.

In the last fifty years, Informatics has developed a series of concepts, tools, processes, methods, theories, etc. to organize the components of artifacts or systems it produces. I am using some of these elements to organize sign relations systematically. In particular, I discuss partial orders in Charles Sanders Peirce's triadic and decadic sign relations. The tools I am referring to are in the scope of data structures, discrete mathematics, and engineering. They include trees, tables, posets, lattices, and Cartesian Coordinate systems. The use of such tools to explore semiotic relations may be a small step, but in my understanding, it is a necessary one to establish an initial common ground.

It is feasible for people in informatics to contribute to semiotics with a systematization of its notation because most of the theory in informatics has been of a monadic nature, what coincides with its emphasis on syntax. Dyadic and triadic models, which could be correlated with the semantic and the pragmatic have not been explored to the same extent. For example, most of the semantics studied in Informatics refer to objects within the computer. Within a Peircean perspective, the understanding of ``meaning'' necessarily triadic. Semantics and pragmatics, if extended to be in consonance with Peirce's philosophy, involve fascinating subjects which need to be pursued in order to ground design as a meaningful communicative activity theoretically, practically, and ethically. My intention is to develop these implications across my future professional practice as an educator.

Chapter 5

Looking Across and Looking Along: Reflections

The categories according to which a group envisages itself, and according to which it represents itself and its specific reality, contribute to the reality of this group.

Pierre Bourdieu, Language & Symbolic Power, p 133, 1991

Well intentioned professionals (those who use invasion not as deliberate ideology but as the expression of their own upbringing) eventually discover that certain of their educational failures must be ascribed, not to the intrinsic inferiority of the ``simple men of the people,'' but to the violence of their own act of invasion. Those who make this discovery face a difficult alternative: they feel the need to renounce invasion, but patterns of domination are so entrenched within them that this renunciation would become a threat to their own identities. To renounce invasion would mean abandoning all myths which nourish invasion, and starting to incarnate dialogical action.

Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, p 137, 1970

Informatics is about technology. Therefore, potentially, it could be about techne and logos. Techne comes from the Greek, and meant art, craft, a human skill grounded ``in general principles and capable of being thought'' [Cambridge Dictionary]. It could also be about information from informare, that in Latin construes as ``to give form to, to describe'' (ibid).

Linking techne and logos, this thesis is about how Informatics has given, is given, and could give form to the general principles of the art and craft of computing. It is about how stakeholders reflect on and intervene upon computational phenomena. The loss of an important file, dream of an intelligent computer, avoidance of a Automated Teller Machine machine due to illiteracy, joy of winning in a computer game, sore back and wrist, meaning of receiving a message from a missing close friend through e-mail, replacement by a robot, all drive different sorts of people to structure their professional lives in consonance and dissonance with everyday culture. This thesis is about people, and their activities, attitudes, values, and world views. It is also about critically reflecting on the good, the bad, and the ugly facets of informatics, on how their blurred boundaries have been co-constructed across theories, practices, and praxis in different disciplines, and on how to describe this complex cultural ecology.

As I was writing these conclusions, I was wondering on how different I would have written this thesis if I had been somewhere else. The main topics of the four chapters would still be present, but probably in a different order and depth. An historical account of Informatics would still be crucial for a critical understanding of where Information Technology is coming from. A discussion on Human-Computer Interaction tendencies would also foster awareness for the future scope of Informatics. Design would continue to link where we come from to where we are going. As a common thread, models in Informatics, HCI, and Design would also be explored in the light of Peirce's work, whose rationale is systematized in a chapter on Semiotics, which could be the first one.

In consonance with Peirce's work the general principles that fostered the development of several conceptual models across this thesis was that thought and action deeply interpenetrate each other across multiple dimensions. I have chosen to explore Peirce because the rationale behind his philosophy goes consistently beyond dichotomously structured understandings of the world, from Mathematics to Practical Sciences, passing through Semiotics. Peirce not only blurred dichotomies, but provided a scaffold to bridge beneath, across, and beyond their isolated falsely presumed nature. In particular, the concepts of mediation and of thirdness could play key roles in overcoming traditional categories that organize not only Informatics, but also Academia and society. They go beneath and beyond because they attempt to explain dichotomies as a possible states of mind/world. In Peirce's Semiotics people are not limited to secondness. When they think/act purposeful and responsibly, they are in thirdness, what also includes secondness. Peirce's criticisms are in consonance with other authors for whom mainstream approaches of cognition and communication were too limited to explain their historically multifaceted nature, such as Mikhail Bakhtin, Pierre Bourdieu, and Paulo Freire. I have not explored their work in this thesis, but I have listed some related work in Appendices D and E.

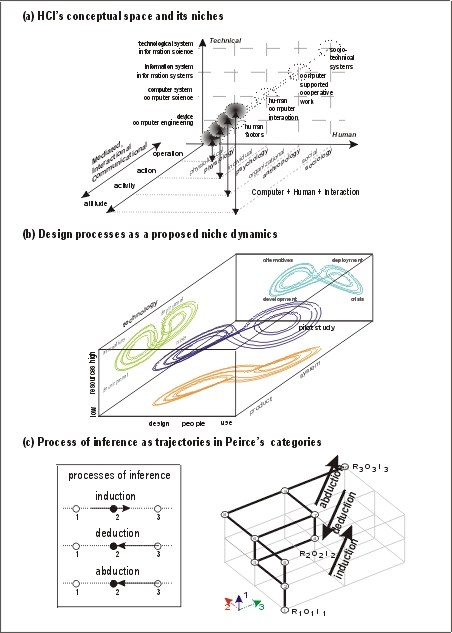

Some related comments are appropriate, and I will develop them in these concluding remarks with the aid of both Figure 5.1, first introduced in the preface, and Figure 5.2, which depicts the core conceptual frameworks proposed across this thesis. The link between, which is not evident in the previous chapters, is briefly discussed below.

Figure 5.1 graphically emphasizes what are the sciences or disciplines discussed and often proposed by Peirce that presuppose Semiotics (Logic) and the ones that are presupposed by it. Semiotics is depicted at the center of Figure 5.1. On one hand, mainstream Informatics has developed theoretical depth in the mathematical facets of the form and structure of computational phenomena (bottom). On the other hand, it has also developed breadth in its actual consequences across society, but not at the same depth (top). In other words, the underpinnings and theoretical tenets of mainstream Informatics are not yet ready to account for the footprint of its social and ethical actual implications and consequences. Metaphorically, mainstream Informatics' reflective frameworks are still mainly focused on wood, being not powerful enough to envision or either see the tree or the forest. To be fair, different branches of Informatics vary in scope on how they see the trees. The long term goal of this thesis is intended to raise awareness of the fact that the wood depends on the tree and the forest, and vice-versa.

It is in my expectations that a future and mature Informatics would take into account the consequences of its professional interventions, theoretically, practically, and politically. This is not yet the case, but a myriad of endeavors have already started to look to Information Technology, and its outcomes (e.g. computers), as if it were open to its environment, as if its artifacts were interactive and mediatory.

Figure 5.2: Main frameworks proposed across the thesis

The conceptual space depicted in Figure 5.2 (a), whose facets are introduced and discussed across Chapters 1 and 2, is intended to describe some of the disciplinary scope across which a broader understanding of Informatics can be explored. The main rationale that informs and structures this framework is ternary, and correlates human, computational, and interactive aspects of human action and the related disciplines that study them. This framework, or conceptual space, is expressive enough to describe disciplinary niches and interdisciplinary relations among activities and disciplines.

Chapter 3, on design processes, was intended to describe the dynamics of disciplinary niches abstractly, such as the ones that link solid state physics, computer engineering, computing science, information systems, information science, and the general public. Most process models across these disciplines remain limited to the scope of their own niches of expertise, assuming that professionals of other disciplines would complete what is not their responsibility within the established socioeconomic order. Most professionals tend not to question where professional demands come from and where they lead to, and this is reflected in the process models that structure their daily activities. For example, developers usually do not critically reflect on the relation between requirements and usability. They indeed structure their professional identities as people that perform those kinds of activities. Linear models of professional workflow (e.g. design process models) abound, but are not capable of reciprocally tieing demand and production.

Indeed most models across Informatics have constellations of interests focused on Information Technology production, rather than use. This can be described with the aid of similar diagrams as the one depicted in Figure 5.2 (b), which visualizes participatory prototyping design process.

Peirce's work also sheds light on the development of this model, which is in accordance with a ternary (Semiotics and Phenomenology) understanding of design processes. It goes beyond most previous models found in the literature, which were dichotomously, linearly and unidirectionally organized. It seems also to be in accordance with part of Peirce's Evolutionary Cosmology, as I explain in the sequel. The process model, fortuitously visualized with the aid of the Lorenz attractor, illustrates (a) the absence of determination through its non-repeatable trajectory, (b) its potential determination with its repeatable but non-periodic pattern, and (c) its habit-taking characteristics as the centripetal and centrifugal forces that attractors can have.

Peirce was not the only one who went beyond traditional models. Other authors have explored with different emphases related problems. I would like to explore in my future work the relation between design and use also in the light of (a) Mikahil M. Bakthin's concepts of heteroglossia (multifaceted), chronotope (centrifugal and centripetal forces), alterity (difference), utterance (dependence on historical and situated conditions), and other concepts of his philosophy of language; (b) Pierre Bourdieu's concept of field and habit, and their relations to orthodox and heterodox forces across societies, as well as his plural concept of capitals, which correlates cultural and material wealth across professions, as well as his reflexive sociology; (c) Paulo Freire's work on progressive education which criticizes dichotomies that separate thinking from doing, teaching from learning, oppressing and oppressed, and so on; and (d) the roots of Pragmatism, including the work of Peirce himself and John Dewey, in which the concept of action is key to education, as it was for Peirce's Semiotics.

As I explored Semiotics as a possible reflective scaffold for Informatics, I understood that there were not much agreement on its foundations. Therefore to accomplish my goal in a sound way it was necessary to clarify its rationale. Peirce's Philosophy (center) investigated the necessary and universal relation between means to ends. This implies purpose, resources, and intention. I doubt that people in traditional Informatics would say that their computers have no purpose. They are aware of the footprint of their professions, and the responsibility towards it. What they are usually not aware of is that the way they think about computing keep these issues out of their concerns.

Awareness for these problems within Informatics have raised renewed interest in Semiotics and other approaches that understand language and interaction in more comprehensive ways than Formal Languages/Lingusitics do. Peirce's Semiotics was part of his philosophy, and had as its close roots Ethics and Esthetics. It was exactly through this relational approach that Peirce attempted to overcome deeply rooted dichotomies through the concept of sign, in its many variants and categories.

Representations, as habit, presuppose action and perception. It is enough to say that in his work discussions on signs and categories are usually accompanied with discussions on sign processes (semiosis) and degenerate signs, which emphasize their relational characteristics.

Peirce's Semiotics was subdivided into three branches, to which he gave different names across his long career. Methodeutic studied knowledge transmission. Critic studied the truth of representation. Speculative Grammar studied signs as signs. The concepts of Syntax, Semantics, and Pragmatics can be correlated with Peirce's semiotics but were organized differently in relation to the structure of sign relations. While Peirce's subdivision is thoroughly triadic, Morris is dyadic. See Figure 4.2 (e), in Chapter 3.

Mainstream theoretical Informatics have been studying computers as computers, as syntax, and studying everything else as such. However, some approaches such as HCI and Software engineering have been concerned with the actual effectiveness of Information Technology use (computers + users) and computer construction (computers + designers), respectively. Still others have been exploring computers as means, as mediations, as signs, and these are usually the approaches that make reference to language studies, including Peircean Semiotics and Cultural Historical Activity Theory. While Peirce's semiotics emphasizes the sign, presupposing action, Activity theory emphasizes activity and outcome, presupposing sign, or tools. In the cultural ecology of Informatics, they have therefore different but complementary foci. That is a topic, not explored here, that could foster a deeper cross-pollination between Semiotics and the Cognitive Sciences.

Most disciplines, however, have stratified their interests across different levels of hierarchies that are assumed independent of each other. In Peirce, they have an inclusive nature, and this is clearly stated as relations of presupposition, as depicted in Figure 5.1. If one understands a sign as action, it is more difficult to fall in the tar pit of either taking the wood for the forest, or imagining a forest without trees. This is not well understood across the literature. Indeed, the same criticisms that I have for the reductionist scope of Informatics I have for Semiotics. This relational and encompassing nature of Peirce's work is not always emphasized by the work of Peirce's followers, with exceptions, who apply his signs and his categories of signs as mere classificatory existential schemata, stratifying and isolating what is enclosed and deeply linked.

At this point in the development of the thesis, I had two alternatives. Firstly, I could have continued with the breadth-first approach exploring areas that have been exploring Semiotics in Informatics. Secondly, I could explore the rationale of Peirce's work in terms of relations. I decided for the second option, because I found that most approaches, although they were explored uncharted terrain and were evidence that the research direction was interesting, were not in agreement with Peirce's framework, at least in my understanding. I do not assume that Peirce is right or wrong. I should also emphasize that I explored neither the conditions of truth of Peirce's Semiotics nor how it has been transmitted, which is a topic of great importance for the further development of Semiotics in Informatics. However, through the systematization developed in Chapter 4, it is possible to say that some interpretations of Peirce's work are in contradiction to it, as shown in Chapter 4.

Chapter 4 presents sign relations and categories of signs as lattices, which was done before, and visualizes them as three-dimensional Hasse diagrams. The visualization is intended to facilitate the understanding of their relational nature. A short example may facilitate the readers understanding of its potentiality. Peirce distinguished two types of abstraction, prescisive and hypostatic. Prescisive abstraction is an explanatory concept that describes processes that go from the particular to the general. Hypostatic abstraction describes the inverted process, from the general to the particular. Among his processes of inference he differentiated between induction, deduction, and abduction. Deduction goes from the general to the particular, as usual. Induction goes from the particular to the direction of the general. Induction is not powerful enough to explain the path towards general laws; it only generalizes a finite set of particular cases. Abductions bridges this gap, explaining the processes, for example of theory building or hypothesis making. Laws are tested against the particular, as illustrated in Figure 3.1 (a).

This can be easily visualized with the 3D Hasse diagram proposed in Chapter 4, as depicted in Figure 5.2 (c) in the case of Peirce's ten categories of ternary signs. The arrows stand for processes of abduction, induction, and deduction that link the traversal of Peirce's ten categories of ternary sign relations, across firstness, secondness, and thirdness.

An area in which the processes of abduction, induction, and deduction could play is Knowledge Representation in Artificial Intelligence. In cognitivist approaches, designers are usually the ones that program the rules into the machine. See Figure 2.3. From the rules, it is possible to deduce what are the steps to be taken to reach a certain goal. Connectionist approaches work by induction, taking particular kinds of samples and ``statistically'' training them through the artificial neural-network. Abduction may play a role in explaining the differences between the two. The above generalization, is usually restricted to the traditional technological dimension that became Informatics' traditional focus. If extended to the human and interactive dimensions, it is possible to see in a different light early projects such as Engelbart's goal to augment human intellect, and more recent ones such as analyzing usage patterns to guide design, or even the inner workings of search engines. The multi-dimensional facets of this framework can also inform and facilitate a critical appraisal of other approaches in the cognitive sciences in which language and instruments play a role as mediatory artifacts, such as distributed cognition (Hutchins), language action (Winograd), situated action (Suchman), and theory of activity (Nardi), among others.

Across the ten categories of ternary signs either one arrives at a state of generality, a law, or not. In the refinement of ternary into decadic signs it is possible to differentiate states of signs that tend to a certain generality (dynamic) but that are not yet in that final state (final). See Figure 4.40 in Chapter 4.

Chapter 4 gives important contributions of Informatics to the field of Semiotics, and indirectly to the approaches in Informatics that are exploring it as a reflective scaffold. Indeed, the language in which signs and its categories are described is made clearer with the aid of structures commonly used in Informatics. I am aware that to understand it in its full depth the reader will need to understand both the structures I am using and the concept of sign relations and categories of signs. I hope that in the long term this may not only facilitate an understanding of Peirce's categories, but also the avoidance of common misunderstandings.

Another topic I would like to explore in Peirce's work in relation to Semiotics is how knowledge is transmitted (Methodeutic) and its conditions of truth (Critic). This would give substance to the abstract structures I discussed in Chapter 4, which may at a first sight be overlooked as either a topic in Informatics, or one in Semiotics. As described, but not commented in Chapter 3, two-dimensional diagrams depicted in Figure 3.11 have been proposed to study genres of interfaces. They played an important role in HCI delimiting different genres of interaction such as command languages and direct manipulation. With that, the previously limited horizon of interaction only as programming was surpassed. These models, or classificatory schemata, indeed went beyond the monadic nature of previous ones. There is no need to say that if there is only one class of things, there is no sense in classifying it. Only when different genres of interfaces started to be expressive enough to be noted did researchers start to classify them in order to better understand their relationship. The extensions were structured on distinctions as objective and subjective, expression and content, manipulation and conversation, individual and collective, and semantic distance. It is when the relations between genres of interaction start to be relevant that two-dimensional models are not powerful enough. Indeed, the addition of a third dimension associated with interaction, with mediation, raises questions about the appropriateness of such schemata to describe phenomena such as learning, working, playing, and others that necessarily happen across time. One of Peirce's achievements was a well thought out framework for ternary semiosis, at least. Therefore, his ten categories could be used as an alternative classificatory scheme to differentiate genres of interaction. I have not explored this issue further, but it is clear for me that any endeavor in Informatics that uses Peirce's semiotics as a scaffold would not do justice to his work if restricted to the level of dyadic semiosis. For example, the use of the second trichotomy (iconic, indexical, and symbolic) as a classificatory scheme is misleading because firstly they are not classes. Secondly, understood in the light of the ten categories they are limited to dyads between the representamen and the object, leaving the interpretant out. A better choice would be to use only the cenopythagorean categories, or the full set of ten categories. People do not do that because these categories are not easily mapped onto traditional genres of interaction. To complicate the matter, some of Peirce's terms such as icons and symbols have meanings in his work that are distinct from their meanings.

Peirce's work was an important scaffold to give structure to this text, but I should stress that the contents of this thesis are not intended to be comprehensive in relation to Peirce's systematic philosophy. However, the thesis does an in-depth study of the general principles that structure Peirce's Semiotics, emphasizing its relational and encompassing character.

This is only at the foundations of his work. If Peirce is right, some fields seem less scientific because they encompass a larger number of difficult problems; because they imply a bigger challenge to reflect and act accordingly. The chasm between Informatics/HCI as a practical science and as a theoretical science is still deep and unexplored, and is exactly where the challenge is. If Informatics indeed represents something to society, and is a changing force (action), this chasm or part of it will have to be explored sooner or later.

END OF: Luiz Ernesto Merkle, "Disciplinary and Semiotic Relations across Human-Computer Interaction"

CONTRIBUTE TO ARISBE Do you think the author has it wrong? If so and you want to contribute a critical comment or commentary, brief or extended, concerning the above paper or its subject-matter, or concerning previous commentary on it, it will be incorporated into this webpage as perspicuously as possible and itself become subject thereby to further critical response, thus contributing to Arisbe as a matrix for dialogue. Your contribution could also be of the nature of a corroboration of the author, of course, or be related to it or to some other response to it in some other relevant way.MORE ON THIS AND ON HOW TO CONTRIBUTE

The URL of this page is:

http://members.door.net/arisbe/menu/library/aboutcsp/merkle/hci-abstract.htm

From the website ARISBE: THE PEIRCE GATEWAY

http://members.door.net/arisbe.

This paper was last modified December 20, 2002

Queries, comments, and suggestions regarding the website to: joseph.ransdell@yahoo.com

TO TOP OF PAGE